Auf einem 63 Lichtjahre entfernten Exoplaneten wurden mit Hilfe des Weltraumteleskops Spitzer Absorptionslinien von Wasserdampf, aber auch Kohlenmonoxid und Methan im Infraroten entdeckt. Der Planet ist ein jupiterähnlicher heißer Gasplanet.

Die dpa meldet eine Entdeckung von Kohlendioxid CO2 mit Hilfe des Hubble Space Teleskops.

Damit ist prinzipiell sicher, dass organische Substanzen in den Atmosphären ferner Planeten entdeckt werden können.

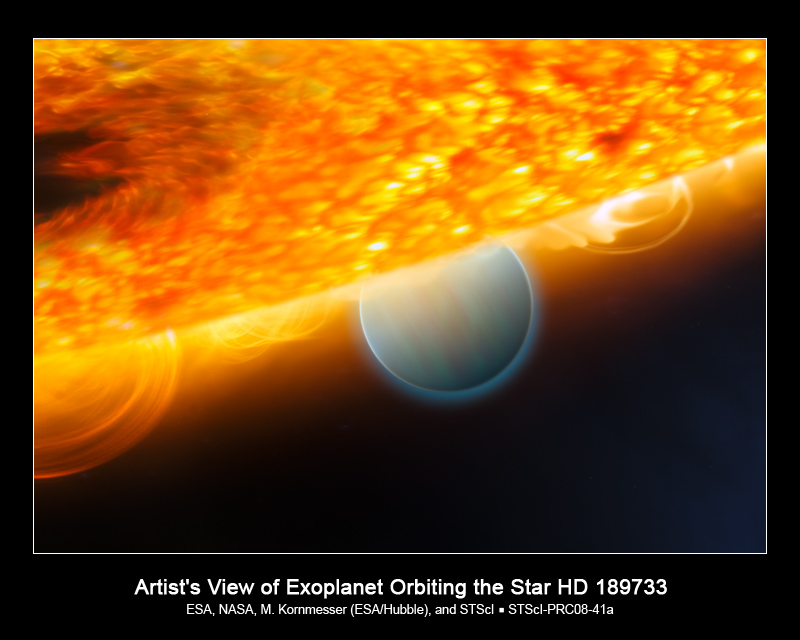

Washington (dpa) - Das Weltraumteleskop «Hubble» hat erstmals Kohlendioxid (CO2) bei einem Planeten eines anderen Sonnensystems nachgewiesen. Dies sei ein wichtiger Meilenstein auf dem Weg, Spuren von Leben auf solchen extrasolaren Planeten im All zu finden, berichtete die US-Raumfahrtbehörde NASA am 9. Dezember in Washington. Der 63 Lichtjahre entfernte Exoplanete HD 189733b im Sternbild Füchschen (Vulpecula) sei zwar zu heiß für Leben. Die Entdeckung zeige aber, dass sich prinzipiell chemische Spuren des Lebens bei Planeten nachweisen lassen, die andere Sterne umkreisen.

Die Wissenschaftler um Mark Swain vom Jet Propulsion Laboratory der NASA hatte mit Hilfe von «Hubbles» Infrarotkamera und einem Spektrometer das Licht von HD 189733b untersucht. Die Gase in der Atmosphäre absorbieren Strahlung bestimmter Wellenlängen. So entsteht eine Art «spektraler Fingerabdruck» der Atmosphärenzusammensetzung, in dem die Forscher auf das Kohlendioxid (CO2) stießen. Auf diese Weise hatte das Team auch bereits Erdgas (Methan), Wasserdampf und Kohlenmonoxid auf demselben Planeten nachgewiesen.

Besonders wichtig sei jedoch das Kohlendioxid: Es könne «unter den richtigen Umständen» eine Verbindung zu biologischer Aktivität anzeigen wie auf der Erde, sagte Swain.

Einen kurzen Film findet man hier!

RELEASE: 08-323

HUBBLE FINDS CARBON DIOXIDE ON AN EXTRASOLAR PLANET

NASA's Hubble Space Telescope has discovered carbon dioxide in the atmosphere of a planet orbiting another star. This is an important step along the trail of finding the chemical biotracers of extraterrestrial life as we know it.

The Jupiter-sized planet, called HD 189733b, is too hot for life. But the Hubble observations are a proof-of-concept demonstration that the basic chemistry for life can be measured on planets orbiting other stars. Organic compounds can also be a by-product of life processes and their detection on an Earth-like planet may someday provide the first evidence of life beyond Earth.

Previous observations of HD 189733b by Hubble and the Spitzer Space Telescope found water vapor. Earlier this year Hubble found methane in the planet's atmosphere.

"Hubble was conceived primarily for observations of the distant universe, yet it is opening a new era of astrophysics and comparative planetary science," said Eric Smith, Hubble Space Telescope program scientist at NASA Headquarters in Washington. "These atmospheric studies will begin to determine the compositions and chemical processes operating on distant worlds orbiting other stars. The future for this newly opened frontier of science is extremely promising as we expect to discover many more molecules in exoplanet atmospheres."

Mark Swain, a research scientist at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif., used Hubble's Near Infrared Camera and Multi-Object Spectrometer (NICMOS) to study infrared light emitted from the planet, which lies 63 light-years away. Gases in the planet's atmosphere absorb certain wavelengths of light from the planet's hot glowing interior. Swain not only identified carbon dioxide, but also carbon monoxide. The molecules leave their own unique spectral fingerprint on the radiation from the planet that reaches Earth. This is the first time a near-infrared emission spectrum has been obtained for an exoplanet.

-more-

-2-

"The carbon dioxide is the main reason for the excitement because under the right circumstances, it could have a connection to biological activity as it does on Earth," Swain said. "The very fact that we're able to detect it and estimate its abundance is significant for the long-term effort of characterizing planets both to find out what they are made of and if they could be a possible host for life."

This type of observation is best done for planets with orbits tilted edge-on to Earth. They routinely pass in front of and then behind their parent stars, phenomena known as eclipses. The planet HD 189733b passes behind its companion star once every 2.2 days. This allows an opportunity to subtract the light of the star alone, when the planet is blocked, from that of the star and planet together prior to eclipse. That isolating the emission of the planet alone and making possible a chemical analysis of its "day-side" atmosphere.

"In this way, we use the eclipse of the planet behind the star to probe the planet's day side, which contains the hottest portions of its atmosphere," said team member Guatam Vasisht of NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory. "We are starting to find the molecules and to figure out how many of them there are to see the changes between the day side and the night side."

This successful demonstration of looking at near-infrared light emitted from a planet is very encouraging for astronomers planning to use NASA's James Webb Space Telescope after it is launched in 2013. These biomarkers are best seen at near-infrared wavelengths. Astronomers look forward to using the James Webb Space Telescope to look spectroscopically for biomarkers on a terrestrial planet the size of Earth or a "super-Earth" several times our planet's mass.

"The Webb telescope should be able to make much more sensitive measurements of these primary and secondary eclipse events," Swain said.

For further information about the Hubble Space Telescope, visit:

http://hubblesite.org/news/2008/41

http://www.nasa.gov/hubble

The Hubble Space Telescope is a project of international cooperation between NASA and the European Space Agency (ESA) and is managed by NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center (GSFC) in Greenbelt, Md. The Space Telescope Science Institute (STScI) conducts Hubble science operations. The institute is operated for NASA by the Association of Universities for Research in Astronomy, Inc., Washington, D.C. STScI is an International Year of Astronomy 2009 (IYA 2009) program partner.